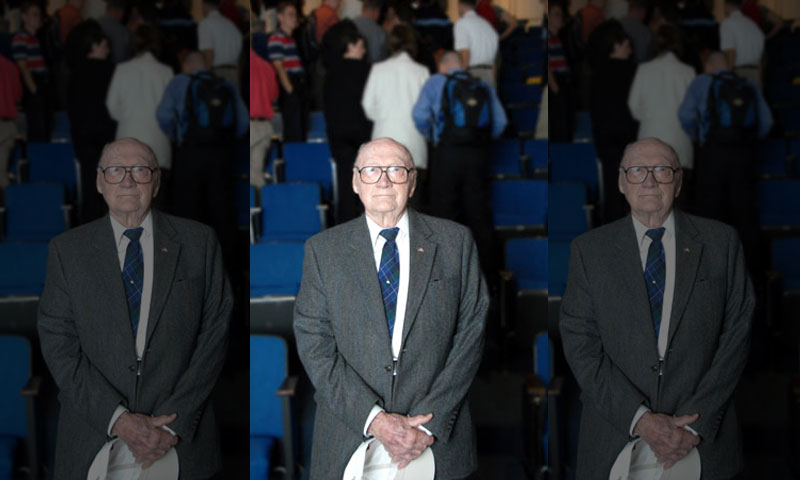

Neil Armstrong’s ‘giant leap for mankind’ would have turned into tragedy had it not been for the fast thinking and courageous action of a Naval Postgraduate School distinguished alumnus, retired Navy Capt. Willard Samuel “Sam” Houston, Jr., who returned to his alma mater to give a special guest lecture.

An aerology graduate (1953) and former meteorology instructor, Houston regaled Space Systems students and members of the Space Systems Academic Group with highlights of his historic career capped with service as Commanding Officer of Fleet Numerical Weather Central (now Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center) also in Monterey.

The theme of Houston’s talk was his direct experience with the gravity of decisions those in command can be called on to make, and the responsibility it places on the meteorologists and oceanographers who advise them.

As a 19-year-old aerographer’s mate at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal Island, Houston recounted, he was called in to see “the Admiral” upon returning from an all-night reconnaissance flight in a twin-engine ‘black cat’ flying low under gathering thunderstorms at sea. The admiral wanted to know if the planes could fly over the cloud tops and whether they’d have enough fuel for the return if the weather turned worse. Houston had to inform the admiral that, given what they’d just flown through and the aircrafts’ fuel capacity, he’d probably lose a third of the pilots on a mission to sink a Japanese cruiser crippled in the northern Solomons. The admiral made the decision to go ahead, as the loss of life would have likely been far greater had he not done so, and the cruiser was sunk at the predicted loss of four planes.

“Ever since that day, I’ve been very aware that a weather forecast may have very serious implications,” he stressed.

By far the most “serious” forecast Houston ever made – and acted on – was for the Apollo 11 moon mission.

Pulled prematurely from a tour in Rota, Spain, Houston had taken command of Fleet Weather Central Pearl Harbor only one day before the historic moon mission where, fortunately, he still had his clearance as the only Naval officer to work with the Air Force’s top secret Corona spy satellite program. As Neil Armstrong and his fellow astronauts were on their way back to Earth, in an abundance of caution, he decided to check the weather at NASA’s programmed splashdown location off Hawaii, at the DMSP readout station at nearby Hickam Air Force Base.

“We were in the Cold War and the technology was closely guarded. The Air Force spy satellite program was kept secret from the other branches of government – even my own superior didn’t know about it,” Houston recalled. “I knew Corona’s orbit would take it over the splashdown area, and wanted more information.”

What he learned from the classified images was that a massive ‘Screaming Eagle’ thunderstorm formation with vertical winds up to 50,000 feet was forming precisely over the watery landing site, which would have ripped the capsule’s parachutes to shreds resulting in instant death of the Astronauts on impact.

Within minutes, Houston was once again before “the” admiral, Rear Adm. Donald Davis, commander of the task force charged with retrieving Apollo 11’s re-entry capsule. Armed with the authority of his certain knowledge that the splashdown location needed to be changed based on having seen the ‘special access required’ images first hand, he was able to convince Davis to move the USS Hornet to the new location before receiving official orders to do so. Houston then convinced NASA’s top meteorologist, who got a national emergency declared to move the atmospheric entry point, and thus the splashdown location, in the nick of time.

Neil Armstrong’s ‘giant leap for mankind’ would have turned into tragedy had it not been for the fast thinking and courageous action of a Naval Postgraduate School distinguished alumnus, retired Navy Capt. Willard Samuel “Sam” Houston, Jr., who returned to his alma mater to give a special guest lecture.

On July 24, 1969, Neil Armstrong’s capsule landed in perfect weather in the Pacific, ticker tape fell like rain and America pulled ahead of the Soviets in the Space Race. NASA ordered a weather reconnaissance flight to the original splashdown location in the Pacific “just to see if I had been crying wolf,” Houston recalled, and found the violent ‘Screaming Eagle’ formation he had seen forming – to an even higher 60,000 feet.

“Again I witnessed the courage of the decision maker who, acting on the advice of a weatherman, made a decision that was professionally risky, but necessary,” Houston said, giving the credit to Adm. Davis.

For his long-secret heroism in saving the Apollo 11 astronauts, Houston was awarded the Navy Commendation Medal by then Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Elmo Zumwalt, Jr. In 1994, the full history of the famous Moon mission was declassified and NPS’ unsung hero was finally able to tell the story, outlined in a 2004 article in DOMAIN magazine.

Houston, who is proud to admit he’s a direct relative of “the” Sam Houston, also recalled his involvement in early experiments in altering the weather. “We put artificial silver iodide into the tops of clouds to artificially stimulate rainfall to relieve the drought in India, and even tried to ‘steer’ a hurricane by flying into its eye,” he said. But his most vivid memory is being in the first aircraft to fly directly into the eye of a typhoon, while with a weather squadron in San Diego. “I was in absolute awe of it,” he said, “and I was scared to death. As they say – no one speaks to God more than the meteorologist.”

“I hope I’ve convinced you that there’s more to being a weatherman than just predicting the weather,” Houston concluded. “Providing the decision maker with the very best scientific data available regardless of the political consequences is the primary role of the military meteorologist, and is an absolute necessity for national security.”

In August of this year, Houston was the capstone speaker at the gala California International Air Show dinner held in the NPS Barbara McNitt Ballroom as part of the university’s 100-Year Centennial Air and Space Week, where he was finally able to tell the whole story about the Apollo 11 Moon mission to seven NPS Astronaut alums and 14 members of the Navy’s Blue Angels.