For the past 30 years, virtual reality has proven to be a foundational technology, one that has completely changed the way humans interact with machines, opening new doors and possibilities that are still being discovered to this day.

Within the Department of Defense (DOD, the impact has been equally powerful, with VR technology fundamentally changing major functions within the department. At the forefront of this advanced technology, first coined ‘virtual reality’ now 30 years ago, is a small graduate university, the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS), and its Modeling, Virtual Environments, and Simulation (MOVES) Institute, where forward-leaning faculty and dedicated students have opened countless doors to uses of VR that are now commonplace throughout the services.

Soldiers and Marines work out new tactics to engage enemies in myriad complex battlegrounds without firing a shot or taking casualties; pilots can crash over and over again in flight-training simulators; surgeons are able to hone their skills without putting human patients at risk; and students can sit in classrooms hundreds of miles away.

NPS students and faculty have persistently pushed the boundaries of immersive technologies: 3D modeling, artificial intelligence, simulation, human-computer interaction and networking. These technologies have transformed the way the U.S. military does business across such disparate areas as virtual rifle ranges, cyber battlefields, logistics, recruitment and aircraft carrier landings.

“Simply put, virtual reality is the technology for moving through and interacting with a three-dimensional computer-generated environment,” explained Dr. Mike Zyda, founder of the MOVES Institute, the group that has spearheaded NPS’ contributions to the field of VR and how the DOD uses it.

This allows for ever more realistic training simulations. Real world challenges, especially high-risk, hazardous or expensive ones, can be practiced over and over again without real world consequences.

“It’s important to rehearse and know what’s where, where you’re going to do what you’re going to do,” Zyda added. “In the heat of battle, once the flash bang goes off, all of your cognitive functions disappear and what remains in your brain are the things that you’ve trained for.”

NPS formally established the MOVES Institute in 2000 to bridge the military analysis work of its Operations Research Department with the simulation and software development expertise of its Computer Science Department. MOVES had existed as an interdisciplinary academic program since 1996, but its origins run much deeper.

In the early 1980s, NPS students began exploring the creation of 3D virtual environments and games on Silicon Graphics Iris 2400 workstations – cutting edge at the time. In 1986, two students developed a FOG-M anti-tank missile simulator as their graduate thesis. The simulator worked brilliantly, accurately modeling the physical dynamics of the real thing.

The only issue was that fire was directed at a stationary target: tanks on a real battlefield tend not to sit still.

“Wouldn’t it be better if it moved around?” recalled Zyda, the students’ advisor. So they developed a way for the missile and the tank to interact in that 3D world, a network they named NPSNET.

“Now we could drive the tank around to evade the missile,” Zyda said. “Next thing you know, we’re building multiple tanks and driving them around.”

This caught the attention of the U.S. Army, which had recently began exploring tank simulators through the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The DARPA effort yielded a system called SIMNET, which came at a hefty $140 million a pop. In contrast, the commercially-available Iris 2400 workstations used by NPS cost $60,000 each.

When the military adopted SIMNET in 1990, few people in the U.S. government understood how to effectively use it, and NPSNET provided a low-cost means to utilize its databases and networking formats. NPS students in the NPSNET group, which would later evolve into the MOVES program, developed hardware and built virtual simulations for a variety of platforms, including aircraft, underwater vehicles, command and control vehicles and forward observers.

“We were doing pioneering things in networking,” Zyda said. “We learned how to build the first fully instrumented body suits that could play across the Internet.”

By 1994, public interest in the Internet had exploded, and startups such as Amazon began their meteoric ascension.

That’s when NPS broke the internet.

Working on a demo of networking capability with the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica, Calif., they requested a few autonomous vehicles. The Rand Corporation sent 2,000. NPSNET handled these magnificently, but the volume of high-priority information packets between the vehicles crashed the Internet all the way from California to Finland, and NPS was soon flooded with ”amazingly hostile” calls asking them to please stop.

“If you did that today, the FBI would probably show up at your door,” Zyda said. “It was just a little test to see the limits of what we could do ... But you know you’re doing your best research when you break things in a big way.”

Even mistakes can have good results – that’s the good thing about scientific research – and the group, soon flush with funding, sought to formally establish the MOVES Institute.

“We had sponsors who would give us big pieces of money and say, ‘please just help us learn how to do this,” Zyda recalled.

Back then, not everyone, even on the NPS campus, was convinced that VR technology was the wave of the future. But with the backing of a three-star admiral and a guaranteed $2 million per year to run the program, the NPS Academic Council approved the MOVES graduate degree program.

“All of a sudden, I had 40 students arrive,” Zyda recalled. “We had a budget and took over the second floor of Spanagel Hall.”

In 1997, Zyda chaired a National Research Council study to explore the vast overlap between military simulation and commercial gaming. Their report, Modeling and Simulation: Linking Entertainment and Defense, fundamentally altered DOD’s use of – and attitude towards – entertainment technology in modeling and simulation systems.

This resulted in what would become a grand slam homerun for the MOVES Institute: it became the birthplace of America’s Army, a first-person shooter video game in which players engage in squad-level tactical combat, immersed in realistic, high-quality environments.

It was launched by the Army in 2002 as a free, downloadable recruiting tool and is still going strong with several million active users logging billions of hours of gameplay time.

“It’s the very first serious game that had a big impact. It became one of the top five played games online in the years that it was out and it was the most successful recruiting tool ever built by the U.S. Army,” Zyda said.

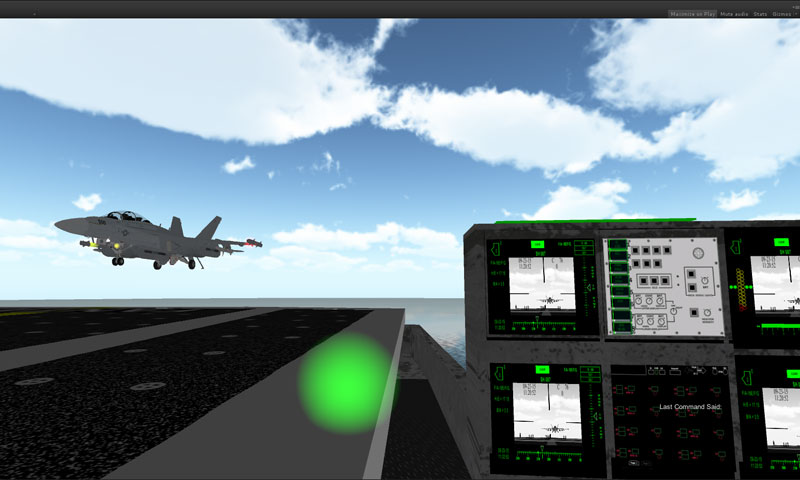

A Landing Signal Officer guides an aircraft to landing as part of a virtual reality trainer developed by Lt. Clay Greunke for his NPS graduate thesis. Photo courtesy of MOVES Institute.

Unlike the carnal gore which defines the genre, America’s Army focuses on team-based, coordinated gameplay among characters using accurately modeled weapons systems. In doing so, the game aims to stimulate interest in the Army for potential recruits.

“The fact that NPS was involved in things like America’s Army was really significant because we recognized that you can immerse people to some degree. The whole idea behind America’s Army was envisioning what it would be like to be in the Army and then trying to use that kind of environment to immerse you in a virtual reality,” said Dr. Imre Balogh, current director of the MOVES Institute.

“It’s not just that we cared about a particular technology, but about creating that virtual environment.”

America’s Army was originally intended as a recruitment tool, but has since morphed into a training tool.

Repurposing its engine has enabled a myriad of virtual reality training simulators, including advance gunnery on the M1A2 Abrams, driving Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles, calling for artillery fire and conducting electronic warfare. A 2016 Government Accountability Office report specifically called on the Army to up its game with virtual reality training in order to confront the world’s increasingly complex security environment.

It’s not just Army, though. All services are heavily investing in virtual reality-based training, such as the Navy’s Fleet Integrated Synthetic Training/Testing Facility (FIST2FAC) on Ford Island, Hawaii.

"This is the future of training for the Navy," said Terry Allard, head of the Office of Naval Research's Warfighter Performance Department. "With simulation, you can explore endless possibilities without the expense and logistical challenges of putting hundreds of ships at sea and aircraft in the sky."

The drive towards virtual reality training is reflective of the efficiency it affords: time, manpower and resources are saved and logistic stress loads lightened. It also provides training opportunities that wouldn’t be possible otherwise, explained Dr. Amela Sadagic, research associate professor with the MOVES Institute.

“A typical example would be emergency procedures for aircraft: some elements of that can be practiced in the real world with real aircraft, but by and large can only be tried and trained in simulators,” she said.

Sadagic cited the thesis work of her former student, Lt. Clay Greunke, as an example. Greunke, a Navy pilot who also served as a Landing Signal Officer (LSO), created a virtual reality training simulator for inexperienced LSOs to practice guiding in aircraft landing on carriers. He had identified a gap in training: LSOs spend a total of six hours in a large, two-story simulator in Oceana, Virginia to work out the fundamentals of landing planes on carriers. Most training occurs on-the-job once new LSOs arrive on a ship, passively observing more seasoned LSOs.

"The first time you go to the aircraft carrier, you have no idea what's going on," Greunke said. "Planes are going by, people are screaming, people are running across the flight deck ... You don't know what to cross, when to cross, what you can and can't do, you are just holding on to the person who's leading you with dear life so you don't get hit."

So Greunke developed a lightweight, portable kit as a “gym bag solution.” The light-weight virtual reality LSO trainer kit can be taken just about anywhere to better familiarize LSOs with flight deck operations and offer refresher training.

For his work, he received honorable mention at the 2016 Secretary of the Navy Innovation Awards – Innovation Scholar (Professional Military Education). The winner was fellow NPS graduate student Lt. Brendan Geoghegan, also an advisee of Sadagic, for his thesis on using virtual reality head-mounted displays to augment ship navigation.

Greunke’s and Geogheghan’s work underscores the unique contribution NPS’ MOVES Institute brings to the field. Advanced virtual reality research is by nature interdisciplinary, and while NPS faculty actively collaborate to share insight from a wide variety of fields – from computer vision to cognitive psychology – students bring to the table a wealth of operational and technical expertise from their diverse military careers.

“The students come in with ideas and then start using those because they’re the ones who have the operational background,” Balogh said. “We enable them to understand virtual reality and they then say,

‘Oh boy, I can see how I can use this to address this particular problem in the military.’ That’s our place.”

This contrasts sharply with civilian academia throughout the rest of the country. Most university simulation programs emphasize cultivation of new skills, and today that emphasis is on the gaming industry. NPS students, already armed with intimate knowledge of their domains, return to their respective services after graduating, bringing new insights directly to end user communities.

“For me, this is unique compared to my colleagues at other universities; they don’t have this proximity to the end users,” Sadagic said. “When it comes to knowledge of a domain, you can’t replicate that.

“Anything that I want to know about aviation, ship navigation or urban warfare, all I need to do is open the door and somebody will know,” she added. “And we do; we do that to a great extent.”

This creates a critical niche for NPS. Thirty years ago, there weren’t many people exploring virtual reality, which meant NPS could be a big fish in a very small pond. The exponential growth of commercial gaming, however, outpaced the institution’s competitiveness in new technology development.

A company like Microsoft, for example, is able to invest in a single product on orders of magnitude several times greater than the entire NPS annual budget. Yet navigating these waters is not a zero-sum game, and the unique position of the MOVES Institute allows it to integrate new technologies to solving complex problems throughout DOD.

“One of the most important things we can do is bring that taught knowledge into the Navy and DOD,” Balogh said. In some ways, then, NPS can act as a clearinghouse of sorts to bring together often disjointed virtual reality technology in application to training requirements across the services.

“We as an entity can get better connections to those pieces of the fleet. We won’t be able to solve all problems, but we can play the role of making sure that all the different efforts connect,” Balogh added.

This unique aspect of NPS was echoed when the Secretary of the Navy shared vision for the future of the university. Addressing students, faculty and staff in February, the Honorable Richard V. Spencer shared how the Navy, DOD and the nation can capitalize on NPS’ strengths.

“I want this institution to be the primary education and research enterprise, with the private sector, government sector and academia coming together at the research level,” he said. “This institution is a primary incubator for the capabilities that we need now.”